|

Tasting Climate Change? The Effects Of Global Warming On Viticulture

By: Thomas M. Ciesla www.charmingwinegeeks.com

|

|

Are you ready for a Sparkling wine from England, or a crisp Icelandic white wine? Don't laugh, if the various computer models predicting additional temperature increases over the next 100 years are correct, these wines could be appearing in a local wine shop near you within decades. Scientists predict global warming may shift wine zones by as much as 500 km by 2100 making today's classic wine regions inhospitable. |

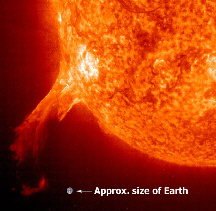

Erupting Solar prominence with approximate Earth size superimposed. Solar image captured by EIT, shown in ionized helium at 108,000 degrees F. | |

|

The theory that mankind's pumping of CO2 into the atmosphere could create a 'global warming' has existed since the 1880's. It wasn't until Mrs. Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister of the UK in 1979 and turned hypothesis into international policy, that the general public became fearful of the consequences. Since then, global warming -- or as it is now called -- 'global climate change', has grown into a sort of political and economic juggernaut for governments, scientists and even the media.

Whether the recent planetary warming trend is caused by industrial age greenhouse gases, or is simply part of the natural climatic cycles of the planet (see sidebar below), is still hotly debated. What is certain, however, is that temperatures have risen 1.3 - 2 degree Celsius over the past 50 years. Researchers point to this increase as the cause of a variety of extreme weather anomalies (hurricanes, El Nino, heat waves), the reduced flow of the Gulf Stream, the increased melting of glaciers, and large reductions in oceanic plankton populations. As temperatures rise, ( models suggest another two degree increase by 2049), various agricultural and viticultural regions of the world will be impacted -- some for the better, some for the worse. | ||

|

Impact On Viticulture Recent warmer temperatures have made vintners very happy, at least in Europe. In France, the last 10-12 years have produced some of the best vintages ever due to the longer, warmer growing season. Cooler climate regions such as Germany's Mosell and Rhine Valleys seemed to have gained the most; early bud break and flowering is now 10 days earlier than the 30 year average. In Britain, historic records show that wine was made there over 2000 years ago, and 1000 years ago during the Medieval Warming. In the 1500's however, temperatures dropped and Europe was in the grips of the Little Ice Age for 300 years. The general warming trend since then has allowed vineyards to flourish again in England. In the New World, Napa Valley may be at a crossroads in the near future. If temperatures continue to increase, the area may exceed optimum climate conditions, says Gregory Jones, climatologist at Southern Oregon University in Ashland. In Napa, the growing season has increased by more than 50 days over the last 75 years, and the grapes often ripen in August when it's hot, rather than in September. Many vineyards are forced to harvest at night when it's cooler, to prevent the start of early fermentation before the grapes reach the winery. In warmer temperatures, winegrowers find more rapid plant growth and out-of-balance flavor profiles in the grapes. A warmer season forces the vine to go through phenological events faster, resulting in earlier sugar levels, without the development of acidity levels which are lost through respiration. The result is 'flabby' wines, with high alcohol levels and little acidity for balance, as well as changes in the aroma profiles.

Sorting Out The Future The global temperature increases predicted over the next 100 years would affect more than grape growing regions around the world. Increased temperatures would impact current 'bread baskets' around the world, melting glaciers will raise sea levels, and changes in weather patterns could leave crops vulnerable to new pests and diseases. |

|

|

|

Water is already a precious resource in many wine regions. Therefore the slightest disruptions in rain patterns would have a significant impact in wine production. For example, the Australian wine industry alone consumes four billion liters of water per year. Increased salinity levels of existing water supplies due to rising sea levels would make the ability to irrigate a growing problem for many of the world's established grape growing regions.

In computer models used at the Hadley Centre, extreme weather conditions are predicted, along with altered rainfall patterns, such as an increase in winter rains and a decrease in summer rainfall. In wine regions with steep slopes, erosion could become a major problem.

|

In Germany, veraison (the point at which ripening begins) is starting 12 days earlier than long term averages. Other grape regions around the world are showing similar treands to early harvest. |

|

Who are the winners and losers in these computer models? In Europe, southern France, Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Italy will be most affected. Even France's Bordeaux region is climatically beginning to resemble Australia's Riverland Districts. In Italy, wine makers are playing down the risk, but there is evidence that there's a significant shift in traditional agricultural areas for olive trees which have almost reached the Alps. The farm lobby, Coldiretti, said that seasonal shifts, fewer but intense rainstorms and the reduction of water reserves could also increase the risk of desertification in some areas.

The winners in Europe will likely be Germany and England. In Germany, vintners are already experimenting with Pinot Noir plantings. Could Merlot be far behind? Of course wine growers will have to deal with new challenges as temperatures increase, such as diseases. Already in Germany, Esca and Black Rot appear regularly, even though 20 years ago such diseases were never seen due to the cold winters. England has experienced a resurgence in grape growing the likes of which haven't been seen since the Little Ice Age. Increased sunshine and warmth have picked up in the last five years, and it's been 15 years since a severe late frost has occurred. For winemakers this translates into an excellent grape harvest with a better acid to sugar balance.

In North America. the models predict that up to 81 percent of premium grape growing acreage could be lost in the United States by 2100. The only areas in California that would remain viable grape regions are the narrow coastal bands and the Sierra Nevada. Wine regions in the southwest and Midwest would all but be eliminated.

The winners would be grape areas farther to the northwest and northeast, such as Oregon, Washington and New York. The problem, however, is that these areas also have high humidity levels, which increases the risk for diseases, translating into higher production costs. Today Canada, a country that only maintains limited wine regions in the Oakanagan Valley in the West and on the Niagara peninsula in the East, could be a major beneficiary of increased temperatures and see a dramatic increase in agriculture in general.

| |

Is it possible that France's Champagne Region could become a minor supplier for sparkling wines by the end of the century? |

What's A Winemaker To Do?

If trends continue, the wine world map will have a much different look. As the wine zone in the northern hemisphere shift northwards, some of the premium wine regions may be found in northern Russia and Canada by 2100. England may become the primary place for sparkling wines. The chalky soils there are similar to that of France's Champagne area; French Champagne growers have recently been buying up land in southern England, where this chalky soil is located. In the southern hemisphere, where there is much less land, it's more difficult to predict the effects of global warming. If temperatures become prohibitive in Australia, (or water becomes a problem), some models see more grape growing potential in Tasmania and New Zealand. In South America, where wine regions are already in arid areas, winemakers are more concerned with the future availability of water than with warmer temperatures. |

|

The reality is that computer models are only as accurate as the data and logic fed into them. The results we've discussed are merely 'best guesses', based on current knowledge, which is always changing. Furthermore, what these models do not incorporate is the human factor; viticulture and viniculture are constantly evolving, and given enough time, most problems are manageable. In the short term, winemakers can no longer afford a myopic view of the world beyond their corner of the vineyard. Just because your growing better grapes now, everyone should be vigilant. First, listen to the grapes, they will tell what's happening and what to do. Second, improve water conservation methods. Third, consider using organic and biodynamic viticulture principals to align the vineyards in better harmony with the local environment. In the long term, winemakers may be forced to try new rootstocks, vinifera varietals, and vine training systems. The impact of climate changes in the vineyard may be decades in the future, but vineyard managers should be documenting what happens from year to year in order to spot trends. This may also be a good time to consider planting long-range experimental vineyards for testing new grape varietals that were never consider before. As indicated in the sidebar on Ice Ages, we are in an interglacial period in the Holocene Ice Age. This interglacial period began about 15,000 years ago, with significant rises in temperature around 12,000 years ago. Everything mankind is today, everything about our civilizations, agriculture, sciences, and collective knowledge was developed in that short time frame. Research indicates that most interglacial periods last from 18,000 - to 22,000 years before the next deep freeze begins. Perhaps somewhere around 6,000 AD, wine regions on Earth will become a mute point and mankind will be more concerned with the terroir of Mars. | |

|

|