When Spanish missionaries came to Texas in the 1600's, wild grapes flourished over the landscape (over 50% of the known species of grape in the world grow in Texas). With a vast diversity in climate and soil, Texas was a grape paradise. Yet, the cultivation of grapes and the production of wine over a 300-year period would seem to take three steps backward for every step forward. We have divided Texas viticulture into 3 steps beginning with the late 1600's.

Viticulture Step 1: Late 1600's-To-Late 1700's

The black Spanish grape reigns supreme

As early as 1650 Father Garcia de San Fancisco y Zuniga, the father of Paso del Norte (today's El Paso) was known for his vineyards and the sacramental wine he produced. The padre brought with him the Spanish black grape (Lenior) as did most padres sent to establish outposts in the vast Texas landscape. Around1680, Spaniards fleeing from Pueblo Revolt in New Mexico established the Senecu, Isletta and Socorro missions in the El Paso area. These missions quickly established vineyards, producing wines, which helped defray the costs of providing the Sacrament of the Eucharist.

During the 1700's, viticulture and wine production remained concentrated in the El Paso area. Irrigation techniques developed by the Franciscan's helped the mission vineyards to flourish. Local farmers also raised grapes to make raisins, wine and the famous Pass brandy. The El Paso area supplied most of the wine and brandy for an area stretching from Chihuahua into New Mexico.

Viticulture Step 2: Late 1700's To Late 1800's

The Mustang grape finds a niche`

In the late 18th century and early 19th century, the El Paso area was a major stop for traders, travelers to Mexico and people travelling west. Many recorded in their journals about 'the magnificent vineyards…from which are made great quantities of delicious wines.' Throughout the early 1800's, El Paso remained a prolific grape producing area, while a smaller planting of grapes popped up around the missions in the Presidio area. This level of resources dedicated to grape production is impressive when you consider that Texas had a total population of 2,500 in the 1820's. In 1830, the Isletta Winery opened in El Paso, and remained in business until the Prohibition.

Amidst the praises sung for Texas wines by various travelers, however, some folks began to object to the quality of the El Paso wines, saying "little of the wine is above mediocrity and it produces headaches." Around this time leading citizens in Juarez, just across the Rio Grande experimented with growing vinifera, only to find as many before that the conditions in far west Texas were inhospitable for most vinifera grapes.

In 1845 Texas was a struggling young Republic (total population of around 124,000), that just agreed to join the United States. The Mexico/American war was raging; there was no industry to speak of and few pleasures. Whiskey was king. Viticulture and wine production were given a shot in the arm in the mid-1800's with the arrival of European immigrants. German immigrants settled in the Hill Country area around New Braunfels, Sister Dale, Frederickburg and Boerne. They discovered the mustang grape and attempted to make palatable wine from it.

In 1860, a time when Ohio led the nation in wine production at 586,000 gallons annually, Steiner's Settlement near Victoria is on record for the production of 2000 gallons of wine from the Mustang grape. In 1863, John Hatch's winery in the San Patricio County was shipping wine to Corpus Christi and other coastal town. In 1870 the Sidney Borden winery in Sharpsburg was shipping a white wine called Sharpburg's Best and a red called Rachel's Choice, named after his wife. In 1875 The Steinberger Winery opened in Windhorst and remained in operation until the Prohibition. Suddenly wine was being produced from the Lenoir and Mustang grape in far reaching counties in Texas.

The German settlers were quickly followed by a wave of Italian immigrants who settled primarily around the eastern Texas, especially the Dallas area. The arrival of Italian immigrants around 1875 in the Dallas area coincided with the exciting work that T.V, Munson was doing in the field of viticulture. A native of Illinois, Munson moved to Denison in 1876 and pursued his loves of grapes. Travelling across all of Texas and forty other states, his work became the definitive source on grapes for horticultural authorities. Munson went on to develop numerous grape hybrids suitable for the Texas environment.

Decades earlier, the parasite oidium ravaged the European vineyards, with the French suffering losses of almost 80 percent. The European wine industry imported native labrusca rootstock from the United States, but these cuttings brought in phylloxera, which attacked the recovering vineyards. In 1868 phylloxera was discovered in southern France; more than 6 million acres of vineyards were destroyed in Europe. The French wine industry requested Munson to send rootstock developed during his studies, where it was grafted with European vinifera. Munson's work along with another horticulturist Hermann Jaeger helped save the European wine industry.

In 1887, not quite a decade since Edison invented the light bulb, the Carminati family opened the Carminati Winery, followed three years later by the Fengolio Winery. The families in this area, particularly the Fengolio's were influenced by the work of T.V. Munson. The Fengolio's raise the Concord grape, Munson developed hybrids, and the Champion, Niagara and Herbemont grapes.

Meanwhile in the border town of Del Rio, another Italian family, the Qualia's quietly established the Val Verde Winery in 1883 with vineyards of the Spanish black grape. The winery was finally permitted in 1885. Sadly, as the 19th century was coming to close, the great vineyards of the El Paso area had all but disappeared. Nature played a part with numerous extended wet and dry periods. Economics also had a part; it became more profitable to raise truck crop produce than viticulture. Finally, the great flood of 1897 washed away a majority of the vineyards in the El Paso area, forcing many to give up the struggle. Though grapes would continue as a crop into the 20th century, this area would never regain its viticulture prominence.

Viticulture Step 3: Late 1800's To Late 1900's

The wine stops, the wine flows

The El Paso area was losing its vineyards but experimental vineyards were cropping up all around the state. The opening of the Fengolio's Winery in 1900 was a harbinger of the activity to come in the Texas wine industry during the early 1900's. Small wineries opened in the Montague, Fredericksburg and Brenham areas as interest in grape culture spread throughout the state.

In 1907, as a severe depression gripped the financial markets, T.V. Munson released his book 'Foundations Of American Grape Culture' which became a standard reference for grape culture in the U.S. During this time agricultural bulletins prophetically proclaimed the advantages of the High Plains and the Trans Pecos areas for vinifera wine grapes

Unfortunately, during the second decade of the 20th century forces were set in motion that would toll the death bell for the Texas wine industry. The temperance movement that started in the late 19th century reached a critical mass with the passage of the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States. Though prohibition was ratified as the law of the land in Texas one year later, most wineries closed down in 1919. Only one winery – Val Verde in Del Rio – would survive through the depression by growing table grapes, and making sacramental wine.

In 1935, Adolf Hitler is Chancellor of Germany as voters in Texas repeal the Prohibition. That fall Val Verde Winery was relicensed and remained the only winery in Texas for many years. To diversify the vineyard, Louis Qualia introduced the Herbemont grape which held the same basic qualities as the Spanish black grape. He also experimented with vinifera, but found they could only survive for few years in the Del Rio area. Probably falling victim to Cotton Root Rot.

At the end of the Prohibition in 1933 and throughout the years of the Depression, the state issued press releases calling for an increase in grape and wine production. In short order, wineries opened in such diverse areas such as Houston, San Antonio, Poteet, Fredericksburg, Brenham, Hondo and Isleta. The wines they produced included Malaga, Port, Burgundy, Sauterne, Sherry, Rhinewine and Claret. Yet grape production remained small; from 1922 to 1946 annual production averaged about 1,800 tons. Despite growing enthusiasm, all but one winery had ceased to exist by the late 1950's. Once again, Val Verde Winery was the lone angel of the Texas wine industry and remained that way until the mid-1970's.

In the late 1960's there was a resurgence of interest in wine across the country, especially in California. Texas was slower to jump on the wine bandwagon, though research efforts had continued since the 1930's through institutes such as Texas A&M University. In the late 1970's vineyards at A&M's Experimental Station in Lubbock began showing promising results for growing vinifera in Texas, something thought to be crucial to creating world-class wines.

The first of a new generation of wineries was bonded in 1975 when Guadalupe Valley Winery opened in the historic village of Gruene, near New Braunfels. Four years later Ed and Susan Auler opened Fall Creek Vineyards on the northern shores of Lake Buchanan. In the 1980's wineries were popping up around Texas like bluebonnets in the spring, thanks to changes in legislation controlling the establishment of small wineries, and important research being done on vinifera cultivars. These were exciting times as the infamous Texas pioneer spirit pushed grape culture and wine production to new heights.

In 1982 Texas produced around 50,000 gallons of wine. Four years later wine production reached around 700,000 gallons. Of course as in any new, dynamic industry change is inevitable and the Texas wine industry was no exception. Of the approximately 29 wineries bonded from 1975 through 1989, 60% of them no longer exist. Despite that turnover rate, today Texas has 33 bonded wineries (if you don't count multiple permits or retail entities with winery permits). With a number of wineries either awaiting permits or in the early planning stages, it's not unreasonable to predict a total of 40 wineries within the next two years.

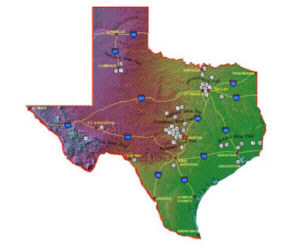

According to Tim Dodd, director of the Texas Wine Research and Marketing Institiute, Texas ranks fifth in wine production behind California, New York, Washington and Oregon. Annual production is consistently over a million gallons, with the majority of that being consumed within Texas. The classic noble grapes dominate Texas viticulture though some exciting experiments are being carried out with new grape varieties. Becker Vineyards in Stonewall has produced a nice Viognier and Alamosa Wine Cellars released their Sangiovese in August of this year. This is the first bottling of this grape as a varietal in Texas. Near New Braunfels, Dry Commal Creek Vineyards has produced a French Columbard, a first for Texas.

STEP 3: TECHNOLOGY

Any vintner will tell you that a wine begins in the vineyard. Without good quality grapes, good wine is impossible. At its most basic level wine is a product of farming. Unarguably the current success level of Texas' wine industry is due in large part to the determined, hard work of a handful of pioneers in the later part of the 20th century. What often goes unsaid, however, is the impact of research in agriculture techniques and technological advancements.

Advances in irrigation techniques, mechanization, and fermentation technology in the second half of the twentieth century have had a tremendous impact in the Texas vineyards.

Where would Texas vintners be without the now common glycol-jacketed stainless steel fermentation tanks? The temperature control -- critical during fermentation -- would be an arduous if not impossible task in the warm Texas climate.

Texas has many challenges for the vineyard manager: Cotton Root Rot, Iron Chlorosis, Nematodes and Phylloxera. A number of rootstock and rootstock hybrids have been developed which often provide protection from more than one vine enemy. For example the Dog Ridge and Salt Creek rootstocks are resistant to both Cotton Root Rot and Nematodes. Champanel is a vigorous rootstock with good Cotton Root Rot resistance and assumed Phylloxera resistance though this has not been proved. Work continues today on rootstocks in experimental vineyards across the state, seeking ways to balance a vine against natural pests and the infamous unpredictable weather in Texas.

What's in the future for Texas wines? One need only look at the past few decades to get a glimpse. The adrenaline-rush activities of the 70' and 80's have settled down to a group of dedicated individuals possessing a true love of wine, who are charting a studied, cautious plan to continue producing premium wines. Each year vintners and vineyard managers learn something new and share that information with the industry as a whole. We may be fifth in production but not in quality or passion.

This concludes this evening's dance session.